the myrtle project

During the pandemic I became fixated on the short life of Myrtle Smith Phibbs, my great grandmother who lived and died in High Point, North Carolina. Maybe it is because she died when she was about my age. Perhaps it is that inevitable tug that leads so many of us to mail off our DNA in search of scraps of our past. Most likely it could be that the pandemic slowed the pace of my life to a 1930s era stroll.

Myrtle ate oysters and planted peas, maintained the family car and sewed dresses. She doted on her three children and put up with her husband’s lack of affection. She helped her parents slaughter hogs every January and would, now and then, ride the train through the night to Washington, D.C. and stay in a lavish hotel. She died in 1935 at the age of 43.

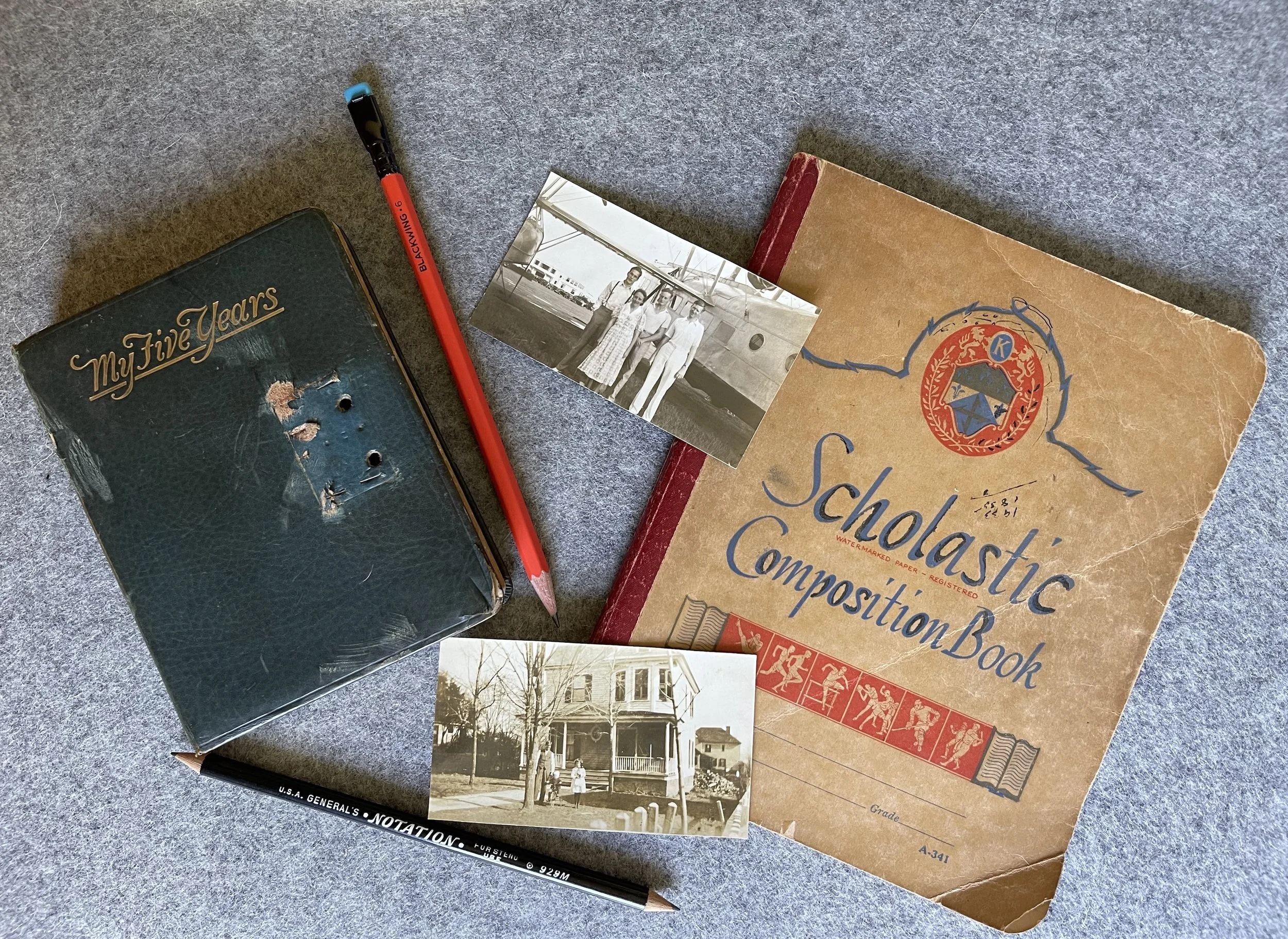

I’ll never know exactly how I came to have her last five diaries. The decision to start reading them was no more than a whim, but after a few pages she felt at once familiar and unknown. She documented the mundane and extraordinary with almost even emotion. The death of a friend and the acquisition of a pound of butter often shared the same sentence.

Myrtle’s husband, William Samuel (W.S.) Phibbs, while mentioned daily, was a distant character. He worked the late shift as a telegraph operator at Southern Railroad -- often reporting to work at 3:00 pm and ending his day at 1:00 am. He did not drive so Myrtle or her eldest daughter (my grandmother, Edith), took him to and from work each day. Myrtle even made additional trips many days to bring him dinner.

Myrtle was a strong woman who was often sad and lonely. Her daily recordings tell a powerful story of one woman constantly working to make her corner of the world beautiful and of how time marches on even when we don’t know where we are in the story.

I set out to read the first diary a day at a time. On January 1, 2020 I read Myrtle’s account of January 1, 1929. Had it not been for the pandemic, I may have kept with this pace. But by August, after repainting three rooms of my house and “Home Editing” all my kitchen cabinets, I was binging an entire diary a week. By the time Dr. Fauci was warning Americans not to gather for Thanksgiving, I’d read all five diaries — twice.

My days often resembled hers – “Cleaned in the a.m., baked a pie in the p.m. I feel bum today.” Once, W.S. brought Myrtle a barbeque sandwich and she was so thrilled she recorded the meal. I got that same high when my husband returned from town bearing gifts of Chinese food or a dozen donuts.

The economic instability was eerily familiar as well. On March 3, 1933 she noted “banks are shaky,” and then a week later, on March 9, she recorded the banks were closed. This was due to President Roosevelt’s nationwide banking closure to allow time to set in place new regulations, another time in our history when something unimaginable and unprecedented happened.

So many events that marked her days were marking mine. Just as I was filling out the 2020 census online, I read her entry about a Mr. Feezer’s visit to the house to take the 1930 census. The week of the 2020 presidential election I read that on November 4, 1930 Myrtle's daughter Edith got up at 5 am to work at the city polls.

Through all these events and non-events Myrtle kept going. She was a decade past the Spanish Flu and in the throes of the Great Depression. She patched clothing, killed chickens, scrubbed floors, and recorded each day’s events. She is heroic to me for her persistence during turbulent times.